DISCLAIMER: The information provided here is for educational purposes only and is designed for use by qualified physicians and other medical professionals. In no way should it be considered as offering medical advice. By referencing this material, you agree not to use this information as medical advice to treat any medical condition in either yourself or others, including but not limited to patients that you are treating. Consult your own physician for any medical issues that you may be having. By referencing this material, you acknowledge the content of the above disclaimer and the general site disclaimer and agree to the terms.

Acute Facial Nerve Paralysis

Overview

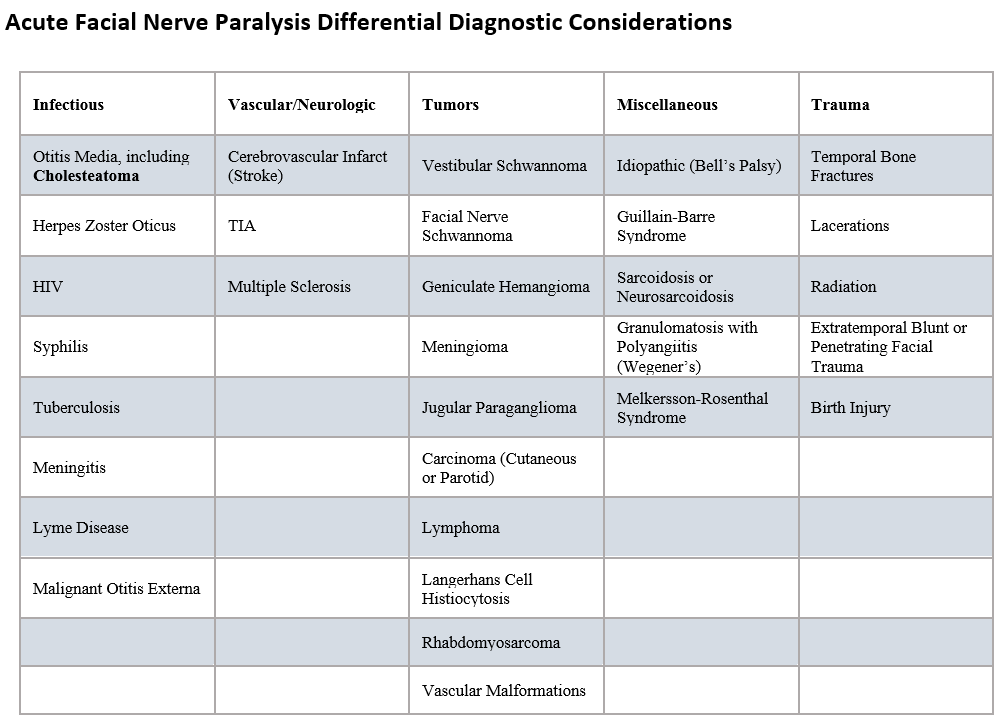

Acute onset paresis or paralysis of the facial nerve, defined as an onset of less than 72 hours, has a wide differential diagnosis including idiopathic or Bell’s palsy, various viral and bacterial infections, skull base osteomyelitis, primary neoplasms (e.g., facial nerve schwannoma, geniculate hemangioma) anywhere along the course of the facial nerve, malignancy with direct or perineural invasion, autoimmune conditions, trauma, and stroke. The focus for this section will be on the appropriate work up and early management strategies for acute facial nerve paralysis with focus on the most common etiology of acute facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy). Facial paralysis secondary to temporal bone trauma, penetrating lacerations, and otitis media is covered in separate respective sections. Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion and the primary concern in the early management of these patients is an accurate diagnosis, early initiation of high dose steroids, consideration for antiviral therapy, and prevention of corneal injury from impaired eye closure. Bell’s palsy presents as a sudden onset unilateral facial weakness that involves weakness of the entire involved hemiface. Some patients experience prodromal otalgia. Bell’s palsy can occur in any demographic, but patients at higher risk include: pregnant women, patients with diabetes, upper respiratory infection, or immunodeficiency. The majority of Bell’s palsy cases show some recovery in facial function within 2-3 weeks of onset. Approximately 70% of Bell’s patients with complete paralysis (House-Brackmann grade VI) and 94% of patients with incomplete paralysis will recover normal facial function within 6 months of onset. Symptoms or signs that should raise suspicion of a cause of acute facial nerve paralysis other than Bell’s palsy include auricular vesicular eruption (Ramsay Hunt, also known as herpes zoster oticus), concomitant cranial neuropathies (skull base pathology or systemic conditions such as GPA or sarcoidosis), otorrhea or middle ear effusion (complicated otitis media or cholesteatoma), target skin rash (Lyme’s disease), indolent progression (malignancy or primary facial nerve tumors), segmental involvement (cutaneous or parotid malignancy), other concomitant neurological symptoms (stroke or other central neurological process), bilateral involvement (systemic disease or Guillain-Barre syndrome), and lack of recovery within 3 months of onset.

Key Supplies for Consultation

Appropriate PPE

Otoscope

512-Hz tuning fork

Management

History

Unilateral or bilateral

Timing and rate of progression

Acute: less than 72 hours and often 24 hours to nadir

Associated symptoms (fever, dizziness, diplopia or other sign of concomitant cranial neuropathy, any pain, otorrhea, dysgeusia, hyperacusis, dysarthria or other neurologic signs etc.)

History of trauma

History of similar events in the past (raises concern of Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome especially if accompanied by facial edema and fissured tongue

History of target rash or vesicular rash around ear

History of ear surgery or other notable ear history

History of other non-melanoma skin cancer or parotid malignancy

Basic medical history including past medical history, medications, allergies, past surgical history, family history, and social history

Physical Exam

Detailed head and neck physical exam with attention to the ear, facial nerve, and other cranial nerves

Otoscopic examination to evaluate ear canal, tympanic membrane, and middle ear

Evaluate for otitis media, ear canal drainage, or evidence of ear canal or middle ear masses

Evaluate for concomitant perichondritis, rash of the ear or ear canal or parotid swelling

Idiopathic facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy) generally demonstrates a normal ear exam

Facial nerve examination usually recorded using the House-Brackmann score (see below) with attention to sparing of upper division or any segmental involvement

Examine skin of face, cheek, upper neck and scalp for malignancy

512-Hertz tuning fork examination

Brief neurological exam (especially critical if anything in history or head and neck exam suggests central process)

Labs and Imaging:

Acute onset facial nerve paralysis without other concerning history or findings is indicative of Bell’s palsy and imaging and labs are not necessary, unless other atypical findings develop or recovery is not seen within 3 months

A temporal bone CT scan may be indicated for evaluation of trauma, or facial nerve paralysis in the setting of complicated otitis media or malignant otitis externa

In the acute setting, CT may be indicated if concern of neurologic process; however, ultimately, a head MRI will likely be required

In most cases, an audiogram is not obtained unless hearing loss is reported

Targeted labs may be indicated if concern of infectious or autoimmune pathology

Treatment of Bell’s Palsy

Initiate high dose systemic steroid treatment within 72 hours of onset; patients should be counseled regarding the risks of systemic steroids, including but not limited to changes in mood, disrupted sleep, increase in blood pressure, increase in blood glucose levels, GI bleed (relatively rare), avascular necrosis of the hip (rare)

Options include prednisone 1mg/kg to max dose of 60mg for 10 days with taper for adults

Strongly consider concomitant GI prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor

Use of antivirals is controversial, but can be considered in the setting of Bell’s palsy and are indicated if suspicion of Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Dosing based on immunocompetency and renal function: Can consider Acyclovir 400mg PO 5x/day or Valacyclovir 1000mg TID for 7 days for adults

If suspicion of Ramsay Hunt, higher dosing warranted and consider Infectious Disease consultation and Ophthalmology consultation if involvement of the orbit

Aggressive eye care to prevent exposure keratitis

Day-time drops (artificial tears)

Night-time eye lubricant

Eye moisture chamber during sleep or tape eye shut

Electrodiagnostic testing in select cases

No electrodiagnostic testing recommended if incomplete paralysis

Can consider electrodiagnostic testing (ENoG) if the patient has a complete unilateral paralysis (HB VI), it has been at least 3 days since onset of paralysis and not more than 14 days since onset of paralysis, and you are considering facial nerve decompression

ENoG showing less than 90% reduction in amplitude compared to the normal side: good prognosis for spontaneous recovery, decompressive surgery not recommended

ENoG showing more than 90% reduction in amplitude compared to normal side: may still recover but worsened prognosis, decompressive surgery may be considered

Close follow up for all patients to assess facial nerve recovery and adequate eye care

Counseling for patients with Bell’s Palsy

Good prognosis for patients with incomplete paralysis: over 90% complete recovery

Fair prognosis for patient with complete paralysis: over 70% complete recovery

Maintain aggressive eye cares

Tight glucose control if diabetic and especially if starting steroids

Should seek medical attention if other neurological symptoms develop

Should re-consider the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy if other symptoms develop or the patient fails to show recovery within 3 months of onset

References:

Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell’s Palsy. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2013;149(3_suppl):S1-S27. doi:10.1177/0194599813505967

Vrabec J.T., Lin J.W. (2013). Acute Facial Nerve Paralysis. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 2503-2518). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Mattox D.E., Vivas E. X. et al (2020). Clinical Disorders of the Facial Nerve. In Flint, P.W., et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 2587-2597). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.