DISCLAIMER: The information provided here is for educational purposes only and is designed for use by qualified physicians and other medical professionals. In no way should it be considered as offering medical advice. By referencing this material, you agree not to use this information as medical advice to treat any medical condition in either yourself or others, including but not limited to patients that you are treating. Consult your own physician for any medical issues that you may be having. By referencing this material, you acknowledge the content of the above disclaimer and the general site disclaimer and agree to the terms.

pediatric otolaryngology TABLE OF CONTENTS:

pediatric otolaryngology ON-CALL CONSULT PODCAST EPISODES:

ACUTE TONSILLITIS

Overview

Acute tonsillitis generally does not require surgical management; however, an understanding of this diagnosis is necessary to differentiate it from peritonsillar cellulitis and abscess, which more frequently require Otolaryngology evaluation and treatment. The key differentiating feature of acute tonsillitis from a peritonsillar process is bilateral and symmetric tonsillar enlargement with uninvolved adjacent structures. In peritonsillar pathology, the soft palate is frequently asymmetrically enlarged or edematous. Most patients with acute tonsillitis, without airway or dehydration concerns, can be managed as outpatients. Treatment generally consists of a 10-day course of penicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, or clindamycin in the case of penicillin allergy or suspicion for mononucleosis. A rapid strep test, or less commonly a throat swab and culture, may be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus) and guide treatment. Patients with pain resulting in poor oral intake may benefit from a 1- or-2-day course of steroids and oral pain medication.

Severe Acute Tonsillitis

Uncommonly, patients may present with dehydration or airway compromise secondary to significantly enlarged tonsils. In younger children, severe acute tonsillitis sometimes requires admission for IV hydration, oral or IV pain medication, IV steroids (e.g., dexamethasone), or IV antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin if mononucleosis is suspected). If there is suspicion for mononucleosis, recall that Monospot® testing may result in a false negative result in the first several weeks, and in the case of high clinical suspicion, diagnosis may require peripheral smear (looking for >50% mononuclear cells and atypical lymphocytes) or viral titers. Also recall that use of amoxicillin and other penicillins may cause a rash in patients with mononucleosis.

When appropriate, patients may be discharged with oral antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for 10 days) and oral pain medication. Patients should have close follow-up scheduled with a Primary Care provider within 2 weeks and the indications to seek earlier medical attention should be clearly communicated.

We recommend the AAO-HNS Clinical Practice Guideline on tonsillectomy in children for additional reading on this topic.

References

1. Christian, J.M., Felts, C.B., Beckman, N.A., et al. (2020). Deep Neck and Odontogenic Infections. In Flint, P.W., et al. (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 141-154). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

2. Jeyakumar, A., Miller, S., Mitchell, R.B. (2013). Adenotonsillar Disease in Children. In Johnson, J.J., Rosen, C.A. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 1430-1444). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Mitchell, R.B., Archer, S.M., Ishman, S.L., et al. (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 160(1_suppl), S1–S42.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

PERITONSILLAR ABSCESS & PHLEGMON

Overview

In contrast to acute tonsillitis, patients with peritonsillar abscess or phlegmon typically present with soft palate edema, erythema, trismus, and otalgia. A distinguishing feature of peritonsillar abscess or phlegmon on physical exam is the inferior medial displacement of the infected tonsil with a contralateral deviation of the uvula. Patients generally appear sick and frequently have a muffled “hot potato” voice, trismus, cervical lymphadenopathy, and sometimes difficulty swallowing secretions. Bilateral abscess is rare but possible.

Peritonsillar abscess and peritonsillar cellulitis/phlegmon can appear similar on physical exam. Peritonsillar phlegmon represents an early stage of infection in which a well-circumscribed abscess has not formed. In some cases of peritonsillar abscess, a fluctuant mass can be palpated along the soft palate. In most cases, CT or ultrasound findings can guide treatment, and can differentiate among peritonsillar abscess, peritonsillar phlegmon, tonsillar abscess, or other deep neck space infections. Although polymicrobial infections are common, Streptococcus pyogenes is the most frequently isolated microbe in peritonsillar abscess.

Key Supplies for Peritonsillar Abscess Drainage Consultation

Headlight

Tongue depressor or retractor

Kidney basin

Suction with Yankauer tip

Flexible laryngoscopy scope

Benzocaine (Hurricane®) or Cetacaine® spray (be aware of risk for methemoglobinemia)

1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine

18-gauge needle (for aspiration of suspected abscess)

27-gauge needle (for injection of submucosa)

12 mL Luer lock syringe

Curved Kelly or hemostat forceps

11- or 15-blade scalpel

Culture swab

Cup of ice water for patient (can gargle to slow bleeding and clear purulence)

Management

In general, it is agreed upon that peritonsillar abscess and peritonsillar phlegmon should be treated with antibiotics. The need for and type of procedural intervention, however, varies across practices. In general, abscesses are drained with either needle aspiration or incision and drainage at bedside, especially when larger than 1.5-2 cm. In loculated abscesses, a true incision and drainage to break up the loculations may be more useful compared to needle aspiration. With smaller abscesses, it may be reasonable to either drain or complete a trial of antibiotics with or without steroids first. Guidelines for patient evaluation and management are listed below.

Perform a complete head and neck physical exam. If there is any concern of airway compromise or obstruction, flexible transnasal laryngoscopy is recommended. Concern of airway obstruction generally requires admission for observation and treatment.

Labs: CBC with differential, renal panel (if considering CT with contrast), rapid strep test, and Monospot® test in young adults.

Imaging: In cases where the location of the abscess is apparent from exam, imaging may not be required prior to drainage. Otherwise, a CT neck with contrast is recommended for targeted drainage. Ultrasound (transcervical or transoral) may be helpful if CT is not available.

Consider treating with oral analgesics, IV fluids, IV dexamethasone, and either IV ampicillin/sulbactam or clindamycin.

After draining the abscess, patients should be discharged on amoxicillin/clavulanate, clindamycin, or an appropriate alternative for 10-14 days. If cultures are sent, antibiotics should be tailored accordingly.

Can also consider discharging with Medrol Dosepak® if significant swelling is present and oral saline/chlorhexidine rinses 4 times daily after incision and drainage.

In rare cases of severe airway obstruction or failed incision and drainage, a quinsy tonsillectomy (at time of infection) may be considered.

Follow-up

Follow-up is recommended for all patients to confirm resolution of abscess or infection.

In cases of first-time peritonsillar abscess in children or adolescents (without other concerning history such as obstructive sleep apnea, recurrent peritonsillar abscesses, or recurrent tonsillitis), follow-up with a pediatrician is reasonable.

In adults, it is important to perform a tonsil exam after the infection has cleared to rule out malignancy as an underlying cause; follow-up with Otolaryngology is recommended.

In patients with recurrent peritonsillar abscess, follow-up with Otolaryngology may be useful for consideration of tonsillectomy.

Procedural Steps for Peritonsillar Abscess Drainage

Obtain written consent from patient noting that there is a 5-20% recurrence rate despite drainage.

Review CT for location of abscess relative to surrounding anatomy and for location of vessels such as the internal carotid artery.

Position patient sitting upright with gown on, holding kidney basin and water to rinse mouth.

Ready equipment, ensure good lighting, and turn suction on with Yankauer tip in place.

Spray peritonsillar area with Benzocaine (Hurricane®) spray (be aware of risk for methemoglobinemia) or another appropriate alternative.

Optional: Palatine nerve block (injection medial to third maxillary molar) using 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000; inject (using 27-gauge needle) in the superior pole of the tonsil and supratonsillar fossa.

Aspirate abscess using 18-gauge needle and 12 mL syringe.

If no significant purulence is aspirated after three attempts, some providers will stop, while others will proceed to open the peritonsillar space.

To open, make a 1-2 cm incision through the mucosa parallel to the anterior tonsillar pillar using a 15-blade scalpel; spread open the incision using a Kelly clamp or similar hemostat and have suction ready.

The open cavity can be flushed with saline or directly suctioned.

Example Procedure Note

Procedure: Peritonsillar abscess drainage

The posterior oropharynx was anesthetized with ___ spray followed by ___cc of ___% lidocaine with ___ epinephrine. An ___-gauge needle with a syringe was inserted across the superior and lateral aspect of the [right, left] tonsil. Aspiration produced approximately ___cc of purulent material, which was sent for cultures. A ___-blade was used to sharply incise the mucosa and access the abscess cavity, which was spread widely open using a curved Kelly clamp. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and the surgical site was hemostatic at the end of the procedure. I expressed to the patient that a combination of antibiotics and open drainage will hopefully lead to their convalescence in 3-5 days. If the patient does not feel better or experiences worsening of symptoms, they are advised to return. I stressed the importance of adhering to the prescribed antibiotic course. The patient expressed understanding and agreement with the plan.

References

1. Christian, J.M., Felts, C.B., Beckman, N.A., et al. (2020). Deep Neck and Odontogenic Infections. In Flint, P.W., et al. (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 141-154). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

2. Jeyakumar, A., Miller, S., Mitchell, R.B. (2013). Adenotonsillar Disease in Children. In Johnson, J.J., Rosen, C.A. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 1430-1444). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Mitchell, R.B., Archer, S.M., Ishman, S.L., et al. (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 160(1_suppl), S1–S42.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

POST-TONSILLECTOMY BLEED

Overview

Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage often represents a surgical emergency. Hemorrhage can either occur within the first 24 hours following surgery (primary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage) or in a delayed fashion, most commonly between days 7-10 following surgery (secondary hemorrhage). Secondary bleeds are the most common, occurring in anywhere between 0.1-4.8% of cases. Hemorrhage after transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oropharyngeal cancer can present similarly in both an acute or delayed fashion and occurs after roughly 5% of TORS cases; in most cases, concomitant ligation of branches of the external carotid artery is performed at or near the time of TORS, which has been shown to reduce the severity of the bleeding, although not the overall post-operative bleed rate.

Key Supplies for Post-Tonsillectomy Bleed Consultation

Headlight

Tongue depressor or retractor

Kidney basin

Suction with Yankauer tip

Benzocaine (Hurricane®) or Cetacaine® spray (be aware of risk for methemoglobinemia)

Silver nitrate

Ice water

Tonsil sponges

Curved ring forceps

Airway cart if active bleeding or airway concerns

Initial Management

When initially consulted for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, the first concern is to verify the patient’s ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation). It is important to ask the Emergency Department to urgently obtain sufficient intravenous access to allow resuscitation and deliver fluids to the patient. In cases of more severe bleeding, it is recommended to obtain a blood type and screen.

Physical exam is crucial to determine whether the patient is actively bleeding (bleeding typically occurs from either the inferior or superior tonsillar poles). Attention to the patient’s airway, vital signs, and pulse oximetry is paramount. Young children may not alert caregivers of bleeding and may simply swallow blood as it accumulates if bleeding is relatively mild, and so physical exam as well as a history of repeated swallowing may be important.

Generally, a child who is actively bleeding (visible hemorrhage or fresh clot in the tonsillar fossa) will require surgical control of hemorrhage. A select group of adults and adolescents without brisk bleeding may be able to tolerate a trial of bedside cautery. Prior to cauterization, gargling ice water may be helpful in slowing down bleeding. All patients should be considered to have a full stomach if sedation or general anesthesia are considered. If proceeding with bedside cauterization, topical anesthetic (e.g., benzocaine or Cetacaine® spray) can be used prior to cauterization with silver nitrate. Prior to cauterization, compression with gauze or a tonsil ball soaked in oxymetazoline and local anesthetic may help with hemorrhage control and local anesthesia. When performing these procedures, it is important to be cognizant of airway stability. It is also important to avoid run-down of silver nitrate onto the larynx, which may cause laryngeal burns or edema.

Should conservative bedside measures fail, the patient will require treatment in the OR for control of oropharyngeal hemorrhage. If the patient is not actively bleeding at the time they are seen or the bleeding is stopped at bedside, observation in the Emergency Department or admission for observation may be appropriate. Factors to consider include the severity of bleeding, patient age and comorbidities, hemoglobin level, reliability of patient to follow directions, and distance the patient lives from the Emergency Department.

Operative Management

In the case of brisk or persistent bleeding in the Emergency Department, or if the patient is unable to cooperate with bedside hemostasis, the OR should be immediately prepared as the patient is rolled back. The patient should be kept upright and given a basin or suction until the time of anesthesia induction to allow expectoration of blood as it accumulates. In some cases, it is possible to hold pressure on the bleeding area with a tonsil sponge on a clamp, but in many cases patients cannot tolerate this. Informed consent should include discussion of damage to oral cavity structures (i.e., lips, teeth), inability to stop bleed, dysphagia, aspiration, and death.

Approaches to securing the airway in these patients vary depending on the situation and the comfort of the Anesthesia team. In the OR, children should generally undergo rapid sequence intubation given the risk of emesis and aspiration. For mild to moderate bleeding or clot, adults may be intubated with videolaryngoscope by the Anesthesia team. The adult patient who is vigorously bleeding but actively protecting his/her airway may be managed with awake fiberoptic intubation. Having operative laryngoscopes and a direct laryngoscopy setup available is also a potential option for rapid transoral intubation by the Otolaryngology team (in this case, ensure that the endotracheal tube will fit through the laryngoscope beforehand). In rare situations, emergent cricothyroidotomy or awake tracheostomy may be required for airway control. Regardless of approach to securing the airway, several suctions, good lighting, and several airway management and rescue options should be ready for use. Keep in mind, patients with postoperative oropharyngeal hemorrhage do not generally die from exsanguination but from airway compromise. Ultimately, airway management in this setting is nuanced and requires the best collective judgment of the Otolaryngology and Anesthesia teams.

Intraoperative technique for hemorrhage control includes use of suction cautery, bipolar cautery, silver nitrate, pillar suturing, and figure-8 suturing. More extreme measures may include cervical approach for ligation of feeding vessels or endovascular procedures.

The stomach should be suctioned clear with a large-bore sump tube at the end of the case; irrigation and suctioning through the tube may be necessary to clear clots from the stomach.

Example Operative Note

PREOPERATIVE DIAGNOSIS: ___

POSTOPERATIVE DIAGNOSIS: ___

PROCEDURE: ___

SURGEON: ___

ASSISTANT: ___

ANESTHESIA: ___ (e.g. GETA, general mask, local)

ESTIMATED BLOOD LOSS: ___

SPECIMENS: ___

INDICATION: ___

KEY FINDINGS: ___

COMPLICATIONS: ___

After written informed consent was obtained, the patient was brought back to the operating room by Anesthesia and placed supine on the operating room table. A surgical pause was performed. Rapid sequence intubation was performed, and the patient was orotracheally intubated without difficulty. The bed was turned 90 degrees. A Crowe-Davis retractor was placed with good visualization of the oropharynx. Eschar was noted in the [left/right] tonsil bed, partially dislodged, with [a small amount of/brisk/pulsatile] bleeding. After a clot was removed, the [left/right] [superior/inferior] tonsillar pole was found to be bleeding more briskly and was controlled with bipolar cautery set at 20. The [left/right] tonsil fossa was examined with no evidence of blood or clot. Valsalva to 30 was performed with no bleeding. The stomach was suctioned with an orogastric tube. The patient was taken out of suspension and the Crowe-Davis retractor was removed. The patient was turned back to Anesthesia in stable condition. The patient was extubated uneventfully.

References

1. Christian, J.M., et al (2020). Deep Neck and Odontogenic Infections. In P.W. Flint, et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 141-154). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

2. Jeyakumar, A., et al (2013). Adenotonsillar Disease in Children. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 1430-1444). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Mitchell, R. B., Archer, S. M., Ishman, S. L., Rosenfeld, R. M., Coles, S., Finestone, S. A., … Nnacheta, L. C. (2019). Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 160(1_suppl), S1–S42.https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818801757.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

PEDIATRIC NOISY BREATHING

Overview

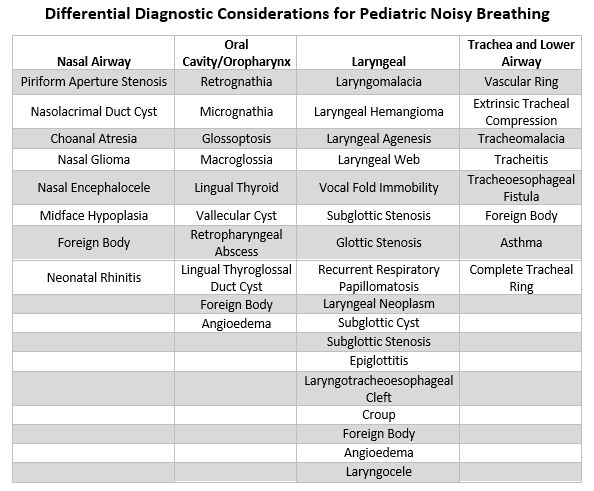

Noisy breathing can take several forms, and characterization of the sound is important to help develop a working differential diagnosis. Stertor can be used to describe any noisy breathing from vibration of tissues superior to the larynx, from the nasal cavity to the oropharynx. Stertor is generally low-pitched and often sounds similar to snoring. Stridor refers specifically to noise produced from laryngeal or tracheal obstruction and is described as high-pitched, musical, or harsh and may occasionally be confused with wheezing (which refers to expiratory noisy breathing originating from the lower airways). After determining the nature of the noisy breathing, it important to characterize its timing during the breathing cycle. Inspiratory stridor, or stridor that occurs while breathing in, usually originates from the supraglottis or glottis. Biphasic stridor, or stridor that occurs during both breathing in and out, generally occurs due to pathology in the subglottis or proximal trachea. Expiratory stridor, or stridor that occurs during breathing out, results from more distal obstruction in the distal trachea, carina, or bronchi. Edema or narrowing of the glottis, subglottis, or proximal trachea may also produce a “barky cough” as commonly seen with croup, also known as laryngotracheobronchitis. These are general guidelines, however, and there are many exceptions. Risk factors for noisy breathing in children include prematurity, history of intubation, uncontrolled gastroesophageal reflux, various anatomic variants, and syndromes including trisomy 21, CHARGE, VACTERL, Pierre Robin sequence, Treacher-Collins, and Beckwith-Wiedemann.

While this section will focus on the most common cause of stridor in infants, laryngomalacia, a broad differential diagnosis during evaluation of pediatric noisy breathing is critical, including pathology from the nasal airway down to the bronchi. Laryngomalacia most commonly presents with progressive inspiratory stridor in infants a few weeks or months old with symptomatic worsening when supine, agitated, or feeding. Hypotonia of the larynx, neurologic immaturity, collapsible redundant supraglottic tissue, and aryepiglottic fold shortening are all factors that may contribute to noisy breathing in laryngomalacia. Awake nasopharyngoscopy with visualization of supraglottic tissue collapse upon inspiration is diagnostic, although the possibility of multilevel airway obstruction should be considered, especially if symptoms are severe. Treatment is guided by the severity of laryngomalacia symptoms, as infants usually outgrow laryngomalacia by 1-2 years of age. Laryngomalacia frequently presents with concomitant acid reflux disease, which should be treated simultaneously in many cases. Mild cases may be treated conservatively with observation and repeat exams. Moderate cases often benefit from upright positioning and thickened feeds and consideration of acid suppression therapy. Severe cases may present with symptoms of failure to thrive, respiratory distress, cyanosis, BRUEs (brief resolved unexplained events), difficulty feeding, or cor pulmonale, which are general indications for surgical intervention with supraglottoplasty. Tracheostomy is almost never necessary for laryngomalacia alone.

Key supplies for Noisy Breathing Consultation

Appropriate PPE including mask, eye protection, gloves, and gown

Headlight

Topical anesthetic/decongestant spray such as lidocaine/oxymetazoline combination (generally not necessary in children 4-5 years of age or younger)

Flexible endoscope (1.9mm vs 2.5mm dependent on patient size), preferably videoendoscopy via portable unit or tower to record exam

Antifog solution (Fred)

Equipment for fiberoptic bronchoscope awake intubation

Management

See all consultations for noisy breathing immediately as acute causes may worsen rapidly. Airway evaluation and potential treatment takes precedence. Signs of impending airway compromise include, but are not limited to, muffled cry; significant lip, tongue, or oral cavity edema; stridor (especially at rest); and distress, anxiety, altered mental status, tachypnea, retractions, cyanosis, tripod or sniffing positioning, and drooling or inability to manage secretions. A history of stridor that becomes less apparent while other signs of distress persist is particularly concerning. When time allows, a history including any prior similar events, witnessed foreign body ingestion, aspiration or recent choking spells, or recent upper respiratory tract illness should be elicited.

If patient is showing signs of airway distress

While talking to the consulting team, recommend placement of IV (although avoid agitating the child if any concern for epiglottitis), oxygen, telemetry, NPO status, and placement of airway cart by patient’s room.

Immediately activate the OR, notify senior resident/attending, Anesthesia team, and OR team, and mobilize help in obtaining airway adjuncts and supplies for intubation or an emergent surgical airway if needed.

Consider oxygen via nasal cannula, nasal trumpet if not contraindicated, facemask, non-rebreather, or Heliox. If available, consider THRIVE (Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange).

In the patient with significant distress, nasopharyngoscopy may be reserved for the OR, although in all but the most extreme cases, fiberoptic airway evaluation may be completed in the Emergency Department and can be performed with a video bronchoscope to facilitate immediate transition to intubation if necessary.

Ideally the airway should be secured in the OR. Generally, intubation over a rod telescope is preferred. Rigid bronchoscopy is an excellent rescue strategy, and flexible bronchoscopic intubation may be helpful in selected cases. However, if the patient is not a good candidate or has acute decompensation, an emergent needle cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy may rarely be required. In general, a surgical cricothyroidotomy is best avoided in younger children if possible, given the risk of long-term sequalae. Emergent surgical airways are rarely needed in pediatric patients, but their rapid decompensation and poor reserve suggest that it is best to be prepared for this possibility.

If the airway is controlled in the OR, consider following with direct laryngoscopy to confirm underlying etiology of airway compromise.

If patient is showing signs of a stable airway

Assess vitals including oxygen saturation and any oxygen requirement, assess the breathing rate, sound (stertor or stridor and phase of sound), work of breathing, nasal flaring, retractions or accessory muscle use, and positionality of the symptoms. Keep in mind that desaturation and bradycardia are late and concerning signs.

Complete history with attention to the timeline regarding onset and progression and any aggravating factors such as supine positioning, agitation, or feeding as well as any symptoms suggestive of significant respiratory compromise such as retractions, cyanosis, apneas, BRUEs (brief resolved unexplained events), need for CPR, weight loss, or failure to thrive.

Assess past airway history including prior intubations and any airway surgeries.

Complete past medical history including birth history, any syndromes or known chromosomal abnormalities, gastroesophageal reflux, medications, past surgical history including any cardiac surgeries, and family history.

Complete head and neck exam focusing on the nasal cavity (fog on mirror under each nostril, nasal airway patency, anterior septum) oral cavity (size of tongue, position of tongue in mouth, size/shape/position of mandible and midface) and oropharynx (tonsils, palatal elevation, size/shape of epiglottis); evaluate for cutaneous hemangiomas in the “beard distribution” as this may be associated with an airway hemangioma.

Assess overall appearance including child size (check growth chart) and skin color. In patients with darker skin tones, the lips and nail beds are useful places to check.

Consider flexible laryngoscopy: Often difficult due to crying, head movement, secretions, etc. Assistance from Nursing staff or parents in holding child still is very helpful. Setting expectations with parents is crucial. If able to record, can be very useful to view later when playback can be slowed or paused. Structures to assess include:

Patency of nasal airway bilaterally and nasopharynx, size and positioning of tongue base, vallecula, piriform sinus, epiglottis (noting size/shape/position), supraglottic structures and soft tissue (noting evidence of redundant tissue or collapse of arytenoids during inhalation), shortened aryepiglottic folds, interarytenoid area, false vocal folds, post cricoid area, glottic larynx (noting mobility of cords, appearance of cords including vascularity, tone, vibration, lesions, webs, stenosis, scarring), and subglottis (evaluate for masses or stenosis). View of the subglottis is often limited in children, and it is rare to get a clear view of the airway beyond this with flexible laryngoscopy alone.

If anterior glottic web present: Genetic screening for 22q11.2 (DiGeorge Syndrome) and cardiac consultation.

If laryngeal cleft or laryngotracheoesophageal cleft: Screening for tracheoesophageal fistula, congenital heart disease, Opitz-Frias syndrome, and trisomy 21.

Imaging

Consider chest x-ray if any concern for pulmonary disease or foreign body.

Consider swallow study for evaluation of aspiration, laryngoesophageal clefts, tracheoesophageal fistula, etc.

Consider MRI brain in cases of bilateral vocal fold paralysis to rule out Arnold-Chiari malformation.

Treatment

If pending respiratory compromise, proceed down airway algorithm to ensure a secure airway and adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Therapy is tailored to the individual diagnosis, but generally requires surgical correction of the airway obstruction in cases of redundant tissue, stenosis, lesions, clefts, or webs.

Laryngomalacia treatment can be subdivided by severity of disease:

Mild disease with inspiratory stridor, no significant feeding impairment or dysphagia, and no clinical or radiographic evidence of second airway lesion: Clinical observation and repeat examinations with optional acid suppression therapy.

Moderate disease with cough, choking, regurgitation, or feeding difficulty: Acid suppression therapy and consideration of swallow evaluation. If trending poorly on growth curve due to feeding difficulties and expending additional effort for respiration during feedings or experiencing aspiration or pulmonary compromise, consider supraglottoplasty.

Severe disease with apnea, cyanosis, failure to thrive, pulmonary hypertension, or cor pulmonale: Acid suppression therapy, swallow evaluation, and strong consideration for surgical intervention with microlaryngoscopy, bronchoscopy, and supraglottoplasty.

Functional endoscopic evaluation of swallow or video fluoroscopic swallow study can be useful adjuncts, especially if concern for aspiration or evidence of failure to thrive. Can consider SEES (static endoscopic evaluation of swallow) for toddlers unable to complete a functional endoscopic evaluation of swallow.

Consider ordering a polysomnogram (sleep study) as an outpatient if concern for obstructive sleep apnea. Keep in mind these studies may be difficult to interpret in young infants and premature babies.

Disposition and Follow-up

Disposition varies based on the underlying etiology and management but have a low threshold to admit if concerns for unsafe airway or rapidly progressive symptoms.

Follow-up usually within 1-2 weeks dependent on the severity of the symptoms and abnormality on exam.

Detailed counseling of return precautions prior to discharge.

References

1. Carter J, Rahbar R, Brigger M, et al. International Pediatric ORL Group (IPOG) laryngomalacia consensus recommendations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;86:256-261. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.007

2. Dohar, J.E., Anne, S. (2013). Stridor, Aspiration, and Cough. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 1338-1355). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Hartl TT, Chadha NK. A systematic review of laryngomalacia and acid reflux. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(4):619-626. doi:10.1177/0194599812452833.

4. Klinginsmith M, Goldman J. Laryngomalacia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; June 11, 2021.

5. Myer CM 3rd, O'Connor DM, Cotton RT. Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103(4 Pt 1):319-323. doi:10.1177/000348949410300410

6. Sidell, D.R., Messner, A.H. (2020). Evaluation and Management of the Pediatric Airway. In Flint, P.W., et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp.3053-3067). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

DEEP NECK SPACE INFECTION

Overview

Deep neck space infections occur across all age groups with various etiologies, although are most commonly caused by an infection of the upper aerodigestive tract (e.g., odontogenic, oropharyngeal, sinonasal). Additional causes include foreign body, malignancy with secondary infection, suppurative lymphadenitis or infection of a congenital tract or fistula (i.e., branchial cleft or thyroglossal duct cyst), or iatrogenic after surgery to the head and neck, trachea, or esophagus. The location of the causative infection typically determines the presentation as well as the offending flora, which is polymicrobial in most cases. Knowledge of the anatomical layers of the cervical fascia is important for understanding tracts of spread and the presenting symptoms. Symptoms primarily depend on the involved space(s) and may include dysphagia/odynophagia (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal), nuchal rigidity (prevertebral), trismus (masticator space with pterygoid involvement), otalgia, dysphonia, and neck pain.

The first concern when evaluating a patient with a potential deep neck space infection is ensuring/establishing a safe airway followed by prevention of disease progression with secondary complications such as Lemierre’s syndrome (septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein with septic pulmonary emboli), mediastinitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, or Ludwig’s angina (firm floor of mouth cellulitis/edema involving the submandibular and sublingual spaces), among others. Mainstays of treatment include securing a safe airway, broad antibiotic coverage (which may be narrowed based on culture data), potential surgical drainage and wound care, and serial exam to ensure improvement. In addition, it is crucial to distinguish these conditions from necrotizing fasciitis – a life-threating, rapidly progressive infection that results in progressive destruction of soft tissue as well as thrombosis of associated vasculature and that requires emergent surgical debridement. Findings concerning for necrotizing fasciitis include, but are not limited to, overlying rapidly progressing erythema and edema, severe pain, fever, crepitus, skin bullae, or ecchymosis. In some cases, symptoms of sepsis including tachycardia, fever, and hypotension may develop.

Layers of Cervical Fascia

Superficial Layer of the Cervical Fascia

Extends from top of head to thorax.

Continuous with platysma, superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), and temporoparietal fascia superiorly.

Deep Cervical Fascia (comprised of 3 layers)

Superficial Layer of Deep Cervical Fascia

Surrounds neck from nuchal line posteriorly, envelops sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, muscles of mastication, and the submandibular and parotid glands.

Middle Layer of Deep Cervical Fascia (comprised of 2 divisions)

Muscular division – envelopes strap muscles (omohyoid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, sternothyroid).

Visceral division – envelopes thyroid, trachea, esophagus, and pharyngeal constrictor muscles; creates buccopharyngeal fascia.

Deep Layer of Deep Cervical Fascia (comprised of 2 layers)

Alar fascia – starts at cranial base and fuses with middle layer of deep cervical fascia in the upper mediastinum.

Prevertebral fascia – starts at cranial base and extends to coccyx.

Both layers are anterior to the vertebral bodies, and envelope the paraspinous muscles.

Carotid sheath fascia is created by all 3 layers of the deep cervical fascia.

Deep Neck Spaces

Parapharyngeal Space

The parapharyngeal space is shaped as an inverted pyramid with base of the pyramid at the skull base and apex at the hyoid bone. The space is divided into pre- and post-styloid compartments and can be thought of as a central space in the neck as it directly abuts the peritonsillar, masticator, parotid, retropharyngeal, and submandibular space with the carotid sheath running through it. Parapharyngeal space infections can both originate from and spread to any of these bordering spaces. An infection in the oropharynx, particularly the tonsil, is one of the most common sources of parapharyngeal space infection. Symptoms reflect this and can be nonspecific (most commonly throat pain, trismus, malaise, and fever) but may less commonly present with neurovascular complications, especially with post-styloid involvement such as mycotic aneurysm, cranial nerve neuropathy, or Horner’s syndrome.

Carotid Sheath Space

The carotid sheath, comprised of all three layers of deep cervical fascia, runs the length of the neck and contains the carotid, internal jugular, vagus nerve, and sympathetic nerve plexus. Infections in this space are most commonly caused by spread from the parapharyngeal space, although rarely IV drug use can lead to an isolated carotid space infection. Involvement of the carotid sheath can present with insidious development of systemic symptoms or fevers weeks after the suspected causative infection and without trismus or other common deep neck space infection symptoms or obvious abnormalities on physical exam, making the diagnosis a challenge. Sentinel bleeding from the oropharynx, nasopharynx, or even ear is thought to occur before many cases of carotid aneurysm rupture and any history of bleeding or neck hematoma on exam should prompt immediate evaluation for this rare but devastating complication.

Retropharyngeal Space

The retropharyngeal space, bounded by the buccopharyngeal fascia anteriorly and the alar fascia posteriorly, extends the length of the neck from skull base to tracheal bifurcation. Its contents include lateral fat pads and lymph nodes that receive drainage from the posterior pharyngeal wall, nasopharynx, middle ear, and nasal cavity. Infections of the retropharyngeal space can be caused by spread from the aforementioned drainage pathways, parapharyngeal space, trauma, recent upper aerodigestive tract surgery, foreign bodies (e.g., fish bone, barbecue brush wire), suppurative retropharyngeal lymph nodes, or spread from a pharyngeal infection. Any patient with fluid/abscess in the retropharyngeal space deserves immediate evaluation, IV antibiotics, and observation in the hospital with possible surgical drainage depending on the clinical picture. Although observed sometimes in children, most adults require surgical drainage, either transoral or transcervical.

Posterior Pharyngeal Wall Layers and Spaces

Prevertebral and Danger Space

Directly posterior to the retropharyngeal space and separated by the alar fascia is the danger space. Bounded by the alar fascia and prevertebral fascia, the danger space receives its name because infections in this neck space have no barrier of spread to the chest and can rapidly lead to mediastinitis or acute necrotizing mediastinitis, which carries a high mortality rate even with appropriate antibiotic coverage and treatment. The prevertebral space is directly posterior to the danger space and extends the length of the spine from skull base to coccyx. The prevertebral space is unique in that most infections occur secondary to vertebral body infections, commonly from spinal hardware, trauma, or tumors.

Submandibular and Sublingual Spaces

These spaces, partially separated by the mylohyoid muscles (with communication around the posterior muscle edge), are commonly involved with periodontal infections while sialadenitis is a less common etiology. Ludwig’s angina, a bilateral submandibular space infection usually due to 2nd or 3rd mandibular molar infections, can rapidly progress to fatal airway obstruction secondary to posterior and superior tongue displacement. Anatomically, infection can spread from the submandibular space to nearby deep neck spaces through the buccopharyngeal gap, created by the styloglossus muscle traversing the pharyngeal constrictors. Oral exam frequently reveals an odontogenic source, oral airway obstruction, and a “woody” induration of the floor of mouth. Airway exam should include nasopharyngoscopy to evaluate the base of tongue, oropharynx, supraglottis, and larynx. A definitive airway should be secured if Ludwig’s angina is suspected as cases can progress to complete airway obstruction rapidly. Adjuncts until a definitive airway is secured/needed include nasal or oral airways, supplemental oxygen, and Heliox (recommended by some sources, although rarely used in the authors experience). THRIVE (Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange) is another recent adjuvant therapy to provide additional airway management time. Most often, videobronchoscopic nasal intubation is the preferred method for definitive airway, although this should only be attempted with a team and equipment ready for an emergent surgical airway. In patients with advanced infection and impending airway distress, awake tracheostomy can be considered. Incision and drainage of any abscess (intraorally for mild disease and transcervical for more severe), drain placement, extraction of the offending tooth (if odontogenic), and broad-spectrum antibiotics are the mainstays of treatment.

Masticator Space

This space contains the muscles of mastication as well as the mandible, inferior alveolar nerve, and internal maxillary artery. Infections of the masticator space predominantly originate from 3rd molar infections. Exam findings are non-specific, most commonly posterolateral oral swelling and tenderness with trismus (involvement of pterygoids). Amalgam artifact can inhibit CT visualization of this space making MRI necessary at times. Drainage may be performed intraorally or externally.

Pretracheal Space

The pretracheal space extends from the thyroid cartilage to the mediastinum. Infection of this space is most commonly iatrogenic following surgical perforation of the anterior esophageal wall but may also be caused by foreign bodies, intubation trauma, or more rarely, thyroid abscess or suppurative thyroiditis. Due to its location, airway edema or compression is possible.

Parotid Space

The parotid space is formed by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia wrapping around the parotid gland. This fascia is deficient at the stylomandibular tunnel allowing communication between the parapharyngeal space and the parotid space. This communication more commonly allows spread of parotid tumors into the parapharyngeal space but may also allow infection to spread between these spaces. Primary infections of this space are most commonly related to sialadenitis and may require drainage in addition to the conservative treatments of parotid massage, warm compress, sialagogues, hydration, and antibiotics.

Key Supplies for Deep Neck Space Infection Consultation

Appropriate PPE including mask, eye protection, gloves, and gown

Headlight

Tongue depressor

Flexible laryngoscope (preferably videoendoscopy via portable unit or tower to record exam)

If planning bedside needle aspiration or incision and drainage

Alcohol pads or betadine swabs

1% lidocaine with 3cc syringe and 27-gauge needle

18-gauge needle and 10cc control syringe for aspiration

+/- use of portable ultrasound for image guided needle aspiration

15-blade

Mosquito or Carmalt forceps

Culture trap or swab (for both aerobic and anaerobic cultures)

Saline irrigation and syringe for irrigation

Suction

Cotton tip applicators

Strip gauze

4x4 gauze

Paper tape

Management

For all patients, airway evaluation comes first. If there are signs of impending airway compromise (e.g., stridor, tripod positioning by patient, desaturation, etc.):

Activate OR, notify your senior resident/faculty, and Anesthesia without delay.

Mobilize support in obtaining airway adjuncts, supplies for intubation, and emergent surgical airway.

If possible, an immediate flexible laryngoscopy is helpful in further determining airway status/site of obstruction and whether intubation would be possible, but airway securement should not be delayed in the emergent setting.

If the patient is stable, obtain a complete history including:

Symptom progression, surgical history (especially recent procedures to the airway or esophagus), dental pain or recent dental work, drug use, recent infection of the head and neck (e.g., sinusitis, otitis media, cellulitis, etc.), past medical history, especially HIV or immunosuppression, TB, diabetes, and any steroid use; pay attention to any “muffling” or inability to complete full sentences due to dyspnea.

Complete head and neck physical exam with attention to oral exam, including Stenson’s and Wharton’s ducts, dental exam, and detailed cranial nerve exam.

Fiberoptic nasopharyngeal airway exam is required in most cases, and certainly if there is any dyspnea/stridor, dysphagia, or dysphonia.

Neck range of motion is particularly important and may be significantly reduced, particularly with retropharyngeal infections.

Labs including CBC and CMP with consideration for blood cultures and wound cultures (if drainage completed) and specific infectious etiologies (e.g., HIV) depending on clinical context.

Imaging can be quite helpful but should never delay securing an airway if there is impending or active airway distress.

CT neck with contrast is preferred in most cases; most modern Emergency Departments can obtain a CT rapidly, and this can provide invaluable information if it is necessary to proceed to the OR.

Plain films of the neck can be considered in an unstable patient with suspected retropharyngeal abscess or supraglottitis but are of less value in the modern setting given access to CT scanners.

Chest radiograph for patients with dyspnea with careful attention to air in the mediastinum, deviation of the trachea, etc.

Ultrasound can be helpful for some neck space infections and may assist in needle aspiration/decompression.

MRI is uncommonly used due to the length of the scan and the need for extended supine positioning in patients who may have airway compromise but can be helpful in stable patients with contrast allergies or if dental artifact obscures the CT.

Low threshold for securing an airway with intubation (either oral or nasal fiberoptic depending on clinical scenario) or awake tracheostomy if intubation is not possible.

Some patients may be observed with medical trial before airway intervention but should be in a closely monitored environment, including consideration of continuous pulse oximetry and capnography, with airway equipment ready in case of decompensation.

At a minimum, admission with close airway observation is indicated in most cases, typically ICU or step-down unit depending on institutional capabilities and the patient’s situation.

Patients are often managed primarily by an ICU team or Medicine team with Otolaryngology and Infectious Disease consultations.

Antibiotics

Initiate empiric broad spectrum antibiotics.

For adults without severe complications or disease, consider ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin.

If severe disease, options include ceftriaxone with clindamycin, ceftriaxone with metronidazole, or penicillin G with gentamicin and clindamycin.

Consider MRSA coverage for at-risk patients with options of clindamycin or vancomycin (dosage dependent on weight and renal function with serum trough levels drawn per local protocol).

Consider antipseudomonal coverage for nosocomial infections with piperacillin-tazobactam or ciprofloxacin.

Consider scheduled steroids if airway concerns, most commonly dexamethasone, but be aware of subsequent impacts to WBC trends after steroid administration and worsening of blood sugar control in diabetics.

Keep all patients NPO during medical trials and have a low threshold to repeat CT neck with contrast if the patient is clinically not responding or deteriorating to assess for the development or progression of a drainable abscess.

General indications for surgical drainage

Abscess, particularly when discrete and greater than 2-3cm (distinct from phlegmon in that the infection is walled off, phlegmon may spread along tissue planes and are not encapsulated and thus more amenable to medical treatment).

Airway compromise.

Failure to respond to medical therapy after 48 hours.

Concern for developing complications (Lemierre’s, Mediastinitis, necrotizing fasciitis, etc.) or disease progression.

Surgical drainage is most commonly performed in the OR depending on the clinical scenario and location of the abscess. Almost always, a passive drain or strip gauze packing is placed to allow continued egress of purulence from the wound and facilitate healing. Large volume irrigation intraoperatively is crucial. Discussion of specific surgical approaches for drainage are beyond the scope of this review, but more information can be found in the included references.

Convalescence

With improving clinical course, patients may be transitioned from intravenous to oral antibiotics, typically guided by susceptibility data from cultures; the Infectious Disease team may assist with determining the course of outpatient antibiotic therapy.

Close follow-up with Otolaryngology after discharge.

Consider repeat imaging once the infection has resolved if suspicion for underlying predisposing pathology such as neoplasm or congenital cyst or tract. For patients with poor dental hygiene, consider dental follow-up to prevent further infections.

References

1. Aynehchi, B.B., Har-El, G. (2013). Deep Neck Infections. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 794-814). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

2. Christian, J.M., et al (2020). Deep Neck and Odontogenic Infections. In P.W. Flint, et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 141-154). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

3. Vieira, F., Allen, S. M., Stocks, R. M., & Thompson, J. W. (2008). Deep neck infection. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America, 41(3), 459–vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.002.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

EPIGLOTTITIS & SUPRAGLOTTITIS

Overview

Epiglottitis is defined by acute inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding supraglottis associated with infection (majority of cases), thermal or chemical inhalation, caustic ingestion, or foreign bodies. The incidence of epiglottitis in children has decreased dramatically since the widespread implementation of a conjugate vaccine for Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Prior to this vaccine, epiglottitis was seen more commonly in children and was characterized by more isolated inflammation of the epiglottis. In adults, the incidence has remained stable with common isolated pathogens including Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes and pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and rarely Candida species in immunosuppressed patients. A viral prodrome or cough may be observed before rapid progression of obstructive airway symptoms and odynophagia. Patients may appear toxic and anxious and may assume the “sniffing position”, with the head hyperextended and nose pointed superiorly in an effort to maintain a patent airway or the “tripod position” by leaning forward to manage secretions. The clinical triad of the ‘‘three Ds’’ (drooling, dysphagia, and distress) constitutes the classic presentation of epiglottitis in both adults and children.

Croup and epiglottitis may be difficult to differentiate in young children but dysphagia/odynophagia, preferred upright or tripod positioning, and drooling are all findings that strongly suggest epiglottitis. Lateral neck x-ray to assess epiglottis thickness (i.e., thumb sign) is sometimes used as a screening tool in the ER setting, with the AP radiograph useful to assess for croup. This may be a reasonable adjunct for evaluating a relatively stable pediatric patient with suggestive findings. For children, laryngeal exam via nasopharyngeal endoscopy or direct laryngoscopy in the OR is required for diagnosis but ideally should take place with preparations for securing an airway. In general, nasopharyngeal endoscopy in the ER is not recommended in children, as lack of easy cooperation and laryngospasm and acute decompensation are more likely to occur than in adults. Nasopharyngoscopy is not strictly contraindicated in children but should be performed by the most experienced Otolaryngology provider available, if at all. Stable adults may carefully undergo videolaryngoscopy (or without video if not available) in the ER setting; however unstable patients should be urgently transported to the OR, where an airway (generally intubation with flexible videobronchoscopic or videolaryngoscopic or surgical if required) can be secured if needed. While many cases present early and can be managed with intravenous antibiotics, steroids, and close airway monitoring, delayed presentation in adults or children may require emergent intubation or a surgical airway. Consequently, upon consultation, the first step is to assess the status of the airway and ensure NPO status, as rapid disease progression may require rapid action to secure the airway. Once diagnosed, antibiotic treatment is highly effective, and inflammation generally resolves within a few days.

Key Supplies for Epiglottitis and Supraglottitis Consultation

Appropriate PPE including mask, eye protection, gloves, and gown

Headlight

Flexible endoscope (preferably videoendoscopy via portable unit or tower to record exam)

Antifog solution (Fred™)

Ensure airway cart is immediately available with supplies for bag valve mask, needle cricothyroidotomy, and surgical airway

Recommend flexible bronchoscope available for intubation if necessary

Management

See all consultations for suspected epiglottitis/supraglottitis emergently.

While talking to the consulting team, recommend placement of IV, oxygen, telemetry, NPO status, and placement of airway cart by patient’s room.

Airway evaluation and management takes precedence. Signs of impending airway compromise include:

Stridor.

Distress, anxiety, or disorientation.

Muffled voice and inability to complete full sentences.

Tachypnea.

Retractions.

Cyanosis.

Sniffing or tripod positioning.

Drooling or inability to manage secretions.

If patient is showing signs of airway distress

Immediately activate OR, notify senior resident/attending, Anesthesia, and OR charge, mobilize help in obtaining airway adjuncts and supplies for intubation or an emergent surgical airway if needed.

Consider oxygen via nasal cannula or facemask, Heliox, or THRIVE (Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange).

Keep patient as calm as possible to discourage airway decompensation; depending on circumstances, may need to avoid provoking maneuvers (e.g., tongue blade exam) in children that may precipitate airway compromise. IV placement should be discussed but should not delay travel to OR to secure airway and should not be done in ER if there is concern for provoking airway compromise.

In the patient with significant distress, nasopharyngeal scope is not generally recommended as this may delay treatment and precipitate airway compromise.

Ideally the airway should be secured in the OR. Generally nasal videobronchoscopic intubation is preferred; however, if a patient is not a good candidate or has acute decompensation, an emergent tracheostomy may be required. Avoid cricothyrotomy in pediatric patients given their anatomy.

After airway is secured, perform direct laryngoscopy.

Evaluate for abscess, which may require incision and drainage.

Obtain cultures if possible.

If patient is showing signs of a stable airway

Complete history including timeline, symptom progression, preceding illness, past medical history. Do not significantly delay airway exam to obtain a lengthy history.

Complete head and neck exam focusing on the airway, oral cavity, oropharynx, and neck.

Ensure airway supplies are readily accessible before exam.

Flexible nasopharyngoscopy

If supraglottic inflammation is significant, proceed with steps as above for impending airway compromise with plan for intubation or surgical airway if needed in the OR.

If supraglottic inflammation is mild, recommend admission to ICU for close airway observation with airway supplies including trach tray at bedside in case of acute decompensation.

Once a stable airway is confirmed or obtained, consider the following labs

CBC, CMP, and CRP for all patients.

If intubated, culture of the epiglottic surface should be taken.

Blood cultures should be ordered in all cases where patients appear toxic and considered in all pediatric cases.

Imaging

Should only be completed in cases of stable airway. Provider should accompany the patient.

AP and lateral neck x-ray.

Sensitive but low specificity.

Quick to perform, doesn’t require patient to lie down.

“Thumb sign” on lateral neck x-ray may indicate edematous epiglottis.

CT neck with contrast.

Sensitive and specific but requires supine positioning, which can lead to rapid decompensation in the scanner.

Better for evaluation of epiglottic abscess, which is more common in adults.

CT should only be considered in patients with a very stable airway, or after the airway has been more definitely secured.

Chest x-ray should be ordered in all cases after airway is secured or patient is in closely monitored environment; concomitant pneumonia may be identified.

Medical treatment

Initiate empiric parenteral antibiotics.

In adults consider 3rd generation cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone) +/- vancomycin for MRSA coverage.

If allergic to cephalosporins, consider levofloxacin or ertapenem with vancomycin.

In immunosuppressed patients with signs of candidiasis on exam, consider intravenous fluconazole or micafungin, usually after consultation with Infectious Disease.

Given the relative rarity of this condition, it may be best to enlist the help of Infectious Disease for input regarding optimal medical therapy.

May consider corticosteroids; however, data regarding benefit are inconsistent.

Admit to ICU.

If intubated, extubate per ICU protocol (e.g., check endotracheal tube cuff leak prior to extubation, etc.).

If not intubated, ensure close monitoring, as airway inflammation and edema can acutely worsen requiring airway securement.

References

Allen, C.T., Nussenbaum, B., Merati, A.L. (2020). Acute and Chronic Laryngopharyngitis. In Flint, P.W., et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 897-905). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Guerra AM, Waseem M. Epiglottitis. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430960

Tibballs, J., & Watson, T. (2011). Symptoms and signs differentiating croup and epiglottitis. Journal of paediatrics and child health, 47(3), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01892.x

Villari, C.R., Statham, M.M. (2013). Infection, Infiltration, and Benign Neoplasms of the Larynx. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 978-988). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Return to Top of Page I Return to Main Survival Guide Table of Contents

AIRWAY & ESOPHAGEAL FOREIGN BODIES

Overview

Foreign body impaction or aspiration requiring Otolaryngology consultation is most commonly seen in pediatric patients, and most frequently involves organic material in the airway and inorganic material with esophageal impactions. All cases require airway evaluation for patency as foreign bodies can lodge in the pharynx or larynx, and esophageal foreign bodies can create pressure and edema that encroach on the posterior trachea leading to airway obstruction, or even erosion into the airway. Furthermore, a co-existing airway foreign body is not uncommon in the setting of a seemingly isolated esophageal foreign body. Most aspiration events lodge the aspirated material in the primary bronchi, right more common than left, unless they are larger in size and obstruct more proximally in the trachea or upper airway. After removal of the foreign body, checking for a second foreign body or secondary aerodigestive injury is critical.

A thorough history that explores the mechanism and nature of the foreign body is important in these cases. If the patient or family member can provide an identical item for study, that can be helpful in instrument selection for removal. Diagnosis is primarily clinical; however, radiographs should be obtained if the patient is clinically stable as they may help localize the foreign body even if it is radiolucent. In many cases the foreign body may be radiopaque (e.g., coin, watch battery, chicken bone); however, a “negative scan” does not rule out the presence of a foreign body because radiolucent material may be missed. It is also prudent to look for indirect signs of foreign bodies including unilateral lung hyperinflation, atelectasis, focal consolidation, surrounding edema, or air in soft tissue surrounding the esophagus or trachea. Persistent sensation of a foreign body that is not visualized by viewing the surface of the mucosa may require a CT to evaluate for embedded fish bone, glass, etc.; this sensation may persist even after the foreign body migrates or is removed secondary to focal mucosal irritation. More proximal foreign bodies in the cooperative older child or adult may be managed in the ER setting; however, those near or below the glottis or at or below the cricopharyngeus will likely require treatment in the OR setting.

Key Supplies for Aerodigestive Tract Foreign Body Consultation

Appropriate PPE including mask, eye protection, gloves, and gown

Headlight

Rigid or flexible endoscope and tower for recording

If available, flexible bronchoscope with working side channel with grasping instruments

Antifog solution (Fred™)

Suction with Yankauer tip

McGill forceps, Carmalt forceps, and curved Kelly clamp

Topical anesthetic/decongestant spray (e.g., lidocaine/oxymetazoline spray)

Ensure airway cart is immediately available with supplies for bag valve mask and surgical airway

Management by Subsites

When managing foreign bodies of the aerodigestive tract, consider approaching these by the suspected site(s) of involvement: oral cavity and oropharynx, tongue base and vallecula, piriform sinus and hypopharynx, supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, trachea, and bronchi.

Oral Cavity/Oropharynx

Oral cavity and oropharynx foreign bodies are often successfully removed by the patient prior to presentation or by the ER provider. In some cases, focal mucosal injury from a prior foreign body that has since migrated distally or has been expelled may induce symptoms that make the patient and provider concerned that it is still present. Small and sharp items, such as fish bones, may also firmly lodge in the oral cavity or oropharynx mucosa making them difficult to immediately visualize. Common areas of the oral cavity and oropharynx that are not easily visualized by other providers include the retromolar trigone, tonsillar fossa, glossotonsillar sulcus, posterior pharyngeal wall, and tongue base/vallecula. In these areas, it is important to examine the painful area as well as the opposing mucosal surface for a potential foreign body. Occasionally, the foreign body will be on the opposite surface from where the patient is experiencing pain. Loupes or a high resolution flexible nasopharyngoscope can be useful to visualize small, difficult to see items, and reflections from a headlight may indicate the location of small foreign bodies.

Tongue base/Vallecula

Foreign bodies at the tongue base/vallecula can sometimes be treated in the Emergency Department (patient tolerance dependent, with great care not to dislodge more distally); however, more distal foreign bodies generally require operative intervention. Mucosal irritation can sometimes be mistaken for a foreign body up to 72 hours after injury; however, in all cases a foreign body must be ruled out. Fish bones, toothpicks, wire brush bristles, etc. are very common foreign bodies at the tongue base/vallecula. The vallecula is optimally visualized by having the patient maximally protrude the tongue while using a flexible nasopharyngoscope through the nose or mouth. “Helping” the patient by gently pulling their tongue forward with gauze may enhance visualization. Depending on the patient’s anatomy, the tongue base and vallecula may be assessed transorally with a good headlight, or more commonly with a flexible scope either through the nose or mouth. One to two puffs of topical anesthetic spray can help with patient tolerance. If there is no concern for airway distress, a lidocaine nebulizer can be very effective at topically anesthetizing the upper aerodigestive tract to allow for good exam and foreign body removal, especially in patients with a strong gag reflex. Foreign bodies that are easily accessible in the tolerant adult patient may be removed in the ER setting; however, in adults who are not tolerant of exam and instrumentation, or when concern for impending airway compromise is present, management in the OR setting is recommended. A portable rigid scope or taping a flexible scope to McGill forceps can be helpful to both visualize and grasp the foreign body. For children, OR removal is strongly recommended. For all patients, avoid use of blind finger sweep as foreign bodies can be pushed distally, and sharp edges may injure the examiner.

Piriform Sinus/Hypopharynx/Supraglottis/Glottis/Subglottis/Trachea/Bronchi

Foreign bodies located more distally are more difficult for the patient to localize, are more challenging to visualize with awake endoscopy, and are more concerning from an airway perspective. Cases of suspected or confirmed foreign bodies involving the supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, or trachea generally require acute intervention. In the stable patient, AP and lateral neck and chest x-rays may be useful to help localize the foreign body. In many cases, flexible nasopharyngoscopy can visualize a foreign body involving the hypopharynx, glottis, immediate subglottis, or esophageal introitus; however, removal in the ER is difficult and the likelihood that the foreign body could be dislodged and move distally is high with manipulation and therefore is generally not advisable. For smaller, biodegradable foreign bodies in adults, time and plenty of fluids may dislodge the foreign body and the patient will swallow it. For larger (or compositionally harmful) foreign bodies, you will likely have to take the patient to the OR. Contact your senior resident, the attending on-call, OR staff, and Anesthesia team as quickly as possible. Regardless of whether an object is visualized on plain film or endoscopy, stories concerning for foreign body aspiration in children generally necessitate an exam in the OR. As a rule of thumb, if any one or more of the three key data elements (history, exam, imaging) is concerning, endoscopy is generally indicated. Assessing these patients quickly when consulted is highly important, as clinical status can rapidly change if the object is obstructing the airway or changes position to cause more complete airway obstruction.

Operating Room Setup

No matter if a child or adult, when proceeding to the OR for airway exam and potential foreign body removal, it is important to ensure that you are set up with all supplies needed to ventilate, expose, examine, and retrieve the foreign body prior to starting the case. When contacting the OR, communicate that you will be performing a microlaryngoscopy, rigid bronchoscopy, possible flexible bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, retrieval of foreign body, and proceed as indicated. If there is a possibility that the foreign body has fragmented, you should request a flexible bronchoscope to allow inspection of the more distal airways. Depending on the clinical status of the patient, you may want to have a tracheostomy tray in the room as well. You will need your institution’s airway/microlaryngoscopy/laryngoscopy cart or instrument pans, appropriate laryngoscopes, the endoscopy tower, topical lidocaine, the 0-degree 4 mm Hopkins rod telescope, McGill forceps, a range of age appropriate bronchoscopes and esophagoscopes (see table below), the foreign body graspers, the peanut graspers, the coin graspers, and suction, etc. If the patient is an infant, consider having tracheoscopes available as well. Have suspension ready if the foreign body is at or above the glottis. Check the lenses and light prisms in everything that has a lens to ensure nothing is broken or cracked before you need it, and remember to focus and white balance your cameras. Confirm that telescopes, suctions, foreign body instruments, and bronchoscopes match in terms of length and diameter. Keep in mind that bronchoscopes and tracheoscopes must be size 3.5 or larger to fit foreign body forceps. If the child is too small to use a 3.5 rigid scope, consider using the laryngoscope and optical foreign body instruments by themselves. Ensure accordion ventilation connectors are available for the bronchoscope. Communicate with the Anesthesia team that the patient’s respiratory status could change quickly and dramatically and ask them to keep the patient breathing spontaneously and to avoid paralysis. Discuss timing of IV access, communicate that the Otolaryngology team will be managing the airway, and again, ensure that you are set up with all supplies needed to expose, examine, ventilate, and retrieve the foreign body prior to starting the case. It is helpful to run through the case in your head, imagining all the instruments and tools you will need, verifying that you have them in working order before the case. Calculate max lidocaine dosage and inform the circulating nurse and surgical tech of this volume and record it somewhere in the OR. If you are confident the foreign body is esophageal, discuss with the Anesthesia team the option to intubate before retrieving the foreign body.

General Guidelines for Operative Procedure

Patient masked down by Anesthesia and handed off to Otolaryngology team; bed generally turned 90 degrees; IV access either before or after mask induction depending on preoperative discussion.

Size appropriate Phillips, Macintosh, or Miller blade or Parsons laryngoscope used to visualize pharynx, larynx, and esophageal inlet with tooth guard.

Many foreign bodies will lodge post cricoid and can be removed with McGill forceps at this point.

Anesthetize glottis with topical lidocaine.

Pause to allow for lidocaine to take effect, mask ventilate.

Re-expose larynx, and advance rigid bronchoscope through vocal cords with care to avoid injury to cords. Remove laryngoscope once rigid bronchoscope is through the cords. Connect circuit to bronchoscope; can provide some ventilation during exam.

Can also place small cuffless endotracheal tube transnasally or transorally, positioned just above glottis to aid in oxygenation. This will not be useful once the bronchoscope is through the vocal cords.

Examine subglottis, trachea, carina, and as far into bronchi as safely possible. If foreign body is visualized, record images, and prepare optical forceps to retrieve object. Turn the head to the right to visualize the left mainstem, and vice versa.

With the appropriate optical forceps (peanut, coin, etc.), the object is grasped, and the entire rigid bronchoscope, forceps, and object are removed as a single unit.

After removal, examine for a “second foreign body” in the trachea/bronchi and esophagus, suction any secretions/blood, look for any aerodigestive tract injuries secondary to the foreign body or its removal, and record images of the airway and esophagus.

Esophageal Foreign Bodies

Overview

Generally, non-food foreign bodies located in the proximal esophagus are frequently managed by Otolaryngology, while food boluses impacted in the esophagus are generally treated by GI unless there are airway issues; however, this division of labor varies by institution. For foreign bodies located in the esophagus, evaluate for airway symptoms as anterior pressure on the trachea and associated edema can cause airway issues. As alluded to earlier, a second foreign body is also possible. Radiographs are particularly important for esophageal foreign bodies. In children, esophageal foreign bodies are frequently inorganic objects (e.g., coins) and usually no underlying esophageal dysfunction is present. Common locations for the foreign body to lodge include at or just below the cricopharyngeus, at the aortic arch, at the level of the left mainstem bronchus, and at the lower esophageal sphincter. It is particularly important to evaluate for possible signs of button battery ingestion. In contrast to coins, a button battery will have a step off sign on lateral projection and halo sign on AP. Button battery ingestion is considered an operative emergency and generally requires expeditious removal, as coagulative necrosis begins soon after mucosal contact (discussed in greater detail below).

In contrast to children, adult esophageal foreign bodies are more likely to be food matter and are more likely to occur in the setting of anatomic abnormality or dysmotility that renders the patient susceptible. In both age groups, the cervical esophagus just distal to the cricopharyngeus muscle is the most common location for the object to become lodged; however, the compression site of the aorta and left main bronchus are all possible locations. Sharp objects such as animal bones and safety pins represent unique situations where timely treatment and removal can prevent serious morbidity. Finally, if there is concern for esophageal perforation, appropriate antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, serial chest films, possible water-soluble oral contrast study, Thoracic Surgery consultation, CT of the chest, and early intervention are generally necessary.

Operating Room Setup and Procedure

Essentially the same as for airway foreign bodies, with the addition of rigid esophagoscopes, which are necessary for foreign body removal beyond the cricopharyngeus muscle. If a known proximal esophageal foreign body is present, this is addressed in the same fashion as an airway foreign body, with attention given to the proximal esophagus upon initial exposure. If the location of the object is unknown, it is prudent to first examine the airway thoroughly. This not only allows for airway foreign bodies to be addressed first, but often, the patient can be intubated after the airway is cleared and focus is turned to the esophagus.

Button Batteries

Overview

Button or disk battery ingestion or intranasal placement occurs most frequently in toddlers and most commonly involves hearing aid batteries or toy batteries. Smaller hearing aid batteries often pass through the GI tract without causing substantial damage due to their small size. Larger button batteries, on the other hand, most commonly become lodged in the upper cervical esophagus. Severe mucosal damage can occur in as little as 1 hour and esophageal perforation in as little at 6 hours with potentially fatal sequelae. Erosion adjacent to major vessels such as the aortic arch may also lead to fatal aorto-enteric fistulae. Identification and localization can usually be achieved with plain film radiography and differentiated from coins by carefully looking for a subtle step off on lateral view or potentially a double-ring or halo sign on AP, reflecting the battery’s bilaminar construction. Theories of the mechanism of damage have evolved over time. Spent or “dead” batteries still frequently retain enough charge to cause damage and independently can cause pressure necrosis, mercury poisoning, or leakage of alkaline contents leading to a liquefactive necrosis in the GI system. Current evidence suggests that ingestion of honey or sucralfate in the field may buffer the battery and reduce injury. Intraoperatively, the site should be copiously irrigated with dilute acetic acid after battery removal. Battery ingestions should be reported to the National Battery Ingestion Hotline at 800-498-8666.

Example Operative Note

PREOPERATIVE DIAGNOSIS: ___

POSTOPERATIVE DIAGNOSIS: ___

PROCEDURE: ___

SURGEON: ___

ASSISTANT: ___

ANESTHESIA: ___ (e.g. GETA, general mask, local)

ESTIMATED BLOOD LOSS: ___

SPECIMENS: ___

INDICATION: ___

KEY FINDINGS: ___

COMPLICATIONS: ___