The information provided here is for educational purposes only and is designed for use by qualified physicians and other medical professionals. In no way should it be considered as offering medical advice. By referencing this material, you agree not to use this information as medical advice to treat any medical condition in either yourself or others, including but not limited to patients that you are treating. Consult your own physician for any medical issues that you may be having. By referencing this material, you acknowledge the content of the above disclaimer and the general site disclaimer and agree to the terms.

Epiglottitis/Supraglottitis

Overview

Epiglottitis is defined by acute inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding supraglottis associated with infection (majority of cases), thermal or chemical inhalation, caustic ingestion or foreign bodies. The incidence of epiglottitis in children has decreased dramatically since the widespread implementation of a conjugate vaccine for Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Prior to this vaccine, epiglottitis was seen more commonly in children and was characterized by more isolated inflammation of the epiglottis. In adults, the incidence has remained stable with common isolated pathogens including Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes and pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and rarely Candida species in immunosuppressed patients. A viral prodrome or cough may be observed before rapid progression of obstructive airway symptoms and odynophagia. Patients may appear toxic and anxious and may assume the ‘‘sniffing position,’’ with the head hyperextended and nose pointed superiorly in an effort to maintain a patent airway or the “tripod position” by leaning forward to manage secretions. The clinical triad of the ‘‘three Ds’’ (drooling, dysphagia, and distress) constitutes the classic presentation of epiglottitis in both adults and children.

Croup and epiglottitis may be difficult to differentiate in young children but dysphagia/odynophagia, preferred upright or tripod positioning, and drooling are all findings that strongly suggest epiglottitis. Lateral neck X-ray to assess epiglottis thickness (i.e., thumb sign) is sometimes used as a screening tool in the ER setting. This may be a reasonable adjunct for evaluating of a relatively stable pediatric patient with suggestive findings. For children, laryngeal examination via nasopharyngeal endoscopy or direct laryngoscopy in the OR is required for diagnosis but ideally should take place with preparations for securing an airway. In general, nasopharyngeal endoscopy in the ER is not recommended in children, as laryngospasm and acute decompensation are more likely to occur than in adults. Nasopharyngoscopy is not strictly contraindicated in children but should be performed by the most experienced otolaryngology provider available, if at all. Stable adults may be carefully scoped in the ER setting; however unstable patients should be urgently transported to the OR, where an airway (intubation or surgical) can be secured if needed. While many cases present early and can be managed with IV antibiotics, steroids, and close airway monitoring, delayed presentation in adults or children may require emergent intubation or a surgical airway. Consequently, upon consultation, the first step is to assess the status of the airway and ensure NPO status, as rapid disease progression may require rapid action to secure the airway. Once diagnosed, antibiotic treatment is highly effective, and inflammation generally resolves within a few days.

Key Supplies for Epiglottitis Consultation

Appropriate PPE including masks, eye protection, gloves, gown

Headlight

Flexible endoscope and tower for recording

Antifog (FRED) solution

Ensure airway cart is immediately available with supplies for bag valve mask, needle cricothyroidotomy, and surgical airway

Management

See all consults for suspected epiglottitis/supraglottitis emergently

While talking to the consulting team, recommend placement of IV, oxygen, telemetry, NPO status, and placement of airway cart by patient’s room

Airway evaluation and management takes precedence. Signs of impending airway compromise include:

Stridor

Distress / anxiety

Tachypnea

Retractions

Cyanosis

Tripod or sniffing positioning

Drooling or unable to manage secretions

If patient is showing signs of airway distress:Immediately activate OR, notify senior resident/attending, anesthesia, and OR charge, mobilize help in obtaining airway adjuncts and supplies for intubation or an emergent surgical airway if needed

Consider oxygen via nasal cannula or face mask, or Heliox

Keep patient as calm as possible to discourage airway decompensation; depending upon circumstances, may need to avoid provoking maneuvers (e.g., tongue blade examination) in children that may precipitate airway compromise. IV placement should be discussed but should not delay travel to OR to secure airway and should not be done in ED if there is concern for provoking airway compromise.

In the patient with significant distress, nasopharyngeal scope is not generally recommended as this may delay treatment and precipitate airway compromise

Ideally the airway should be secured in the OR. Generally nasal fiberoptic intubation is preferred, however, if a patient is not a good candidate or has acute decompensation, an emergent tracheotomy may be required

After airway is secured, perform direct laryngoscopy

Evaluate for abscess, which may require incision and drainage

Obtain cultures if possible

If patient is showing signs of a stable airway:Complete history including timeline, symptom progression, preceding illness, past medical history. Do not significantly delay airway examination to obtain a lengthy history

Complete head and neck exam focusing on the airway, oral cavity, oropharynx, and neck

Ensure airway supplies are readily accessible before exam

Flexible nasopharyngoscopy

If significant supraglottic inflammation, proceed with steps as above for impending airway compromise with plan for intubation or surgical airway if needed in the OR

If supraglottic inflammation is mild, recommend admission to ICU for close airway observation with airway supplies including trach tray at bedside in case of acute decompensation

Once a stable airway is confirmed or obtained, consider the following labs:

CBC, CMP, and CRP for all patients (after airway is secured if required)

If intubated, culture of the epiglottic surface should be taken

Blood cultures should be ordered in all cases where patients appear toxic and considered in all pediatric cases

Imaging

Should only be completed in cases of stable airway. Provider should accompany the patient

AP and lateral neck x-ray:

Sensitive but low specificity

Quick to perform, doesn’t require patient to lie down

“Thumb sign” on lateral neck x-ray indicates edematous epiglottis

CT neck with contrast:

Sensitive and specific but requires supine positioning

Better for evaluation of epiglottic abscess, which is more common in adults

CT imaging should only be considered in patients with a very stable airway, or after the airway has been more definitely secured

Chest x-ray: should be ordered in all cases after airway is secured or patient is in closely monitored environment; concomitant pneumonia may be identified

Medical treatment

Initiate empiric parenteral antibiotics

In adults consider 3rd generation cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone) +/- vancomycin (MRSA coverage)

If allergic to cephalosporins, consider levofloxacin or ertapenem with vancomycin

In immunosuppressed patients with signs of candidiasis on exam, consider IV fluconazole or micafungin, usually after consultation with Infectious Disease

Given the relative rarity of this condition, it may be best to enlist the help of infectious disease for input regarding optimal medical therapy

May consider corticosteroids; however, data regarding benefit is inconsistent

Admit to ICU

If intubated, extubate per usual ICU protocol (e.g., check ETT cuff leak prior to extubation etc.)

If not intubated, ensure close monitoring, as airway inflammation and edema can acutely worsen requiring airway securement

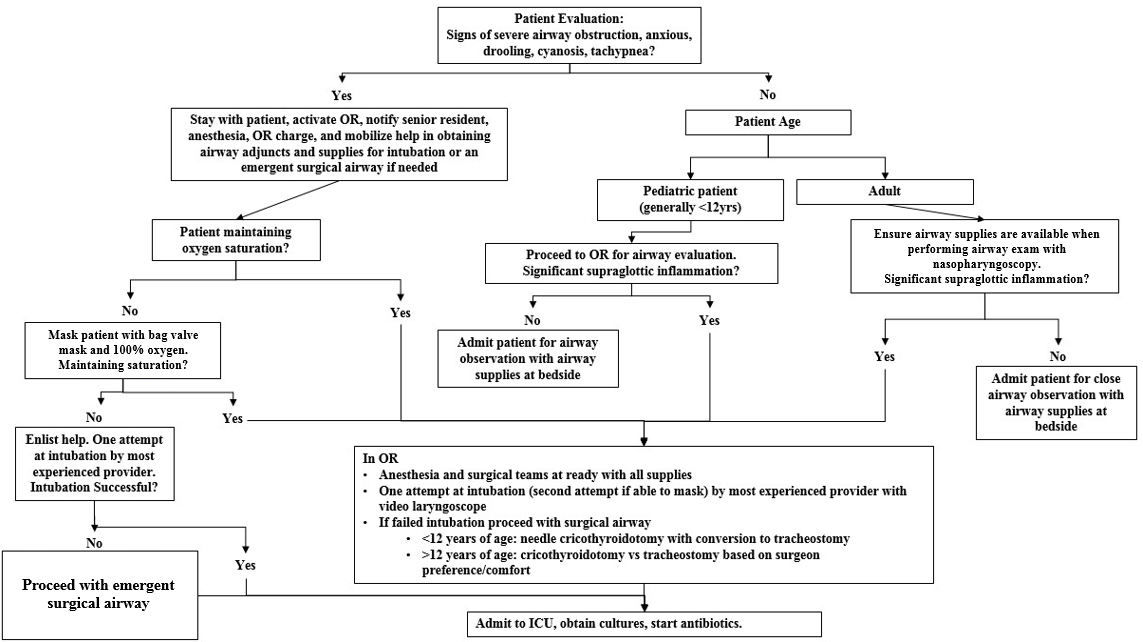

Airway algorithm for epiglottitis/supraglottitis to provide a general framework; all decisions must be made by qualified provider(s) according to clinical context.

References

Allen, C.T., Nussenbaum, B., Merati, A.L. (2020). Acute and Chronic Laryngopharyngitis. In Flint, P.W., et al (Eds.), Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 7e (pp. 897-905). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Guerra AM, Waseem M. Epiglottitis. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430960

Tibballs, J., & Watson, T. (2011). Symptoms and signs differentiating croup and epiglottitis. Journal of paediatrics and child health, 47(3), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01892.x

Villari, C.R., Statham, M.M. (2013). Infection, Infiltration, and Benign Neoplasms of the Larynx. In J.J. Johnson, C.A. Rosen. (Eds.), Bailey’s Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology 5e (pp. 978-988). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.