"Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive. Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive."

It was my last day in the PICU and last day on pediatrics. I had come in at my usual time of 5:30 to pre-round on my patients. One I had carried for a week and was very familiar with and the other was a little boy with an epidural for who most of the heavy lifting had been done overnight. 7:30 came, I presented my last 2 patients, and rounds flew by, finishing ahead of time mostly due to our light census. It was looking like it was going to be a light last day, and that I would have time to fit in some much-needed studying for my shelf exam the next day. It was 8:30am and I had just settled down with a paper on PRVC ventilation when the voice on the overhead speaker system chimed on: "Code 99, 9th floor, room 4. Code 99, 9th floor, room 4."

The PICU chief takes off running down the hallway, the team a few meters behind. We arrive up at the code in under a minute, finding ourselves the first responders due to the fact that most of the attendings and residents in the hospital were a building over in morning report. Our team would be running this code.

A code in real life is nothing like in the television shows (big surprise). It is a much more controlled chaos. There isn't any yelling, pounding on chests, doctors screaming "don't quit on me! DON'T QUIT ON ME!," or any of the other stereotypes that people think of when you say the words "code blue." We had actually had a mock code for the residents and students with a sim-patient the week before - our institution is big on assigned roles and closed loop communication. So I settled into my role of information gatherer and runner: finding the patient's most recent labs in her chart, getting ice to cool the patient's body, running blood gases down to the PICU, etc.

The patient was a 3 year old little girl who was actually set to be discharged later in the day. She had nephrotic syndrome and had spent half a day in the PICU earlier in the week with some mild pulmonary edema. Her labs looked completely normal and she hadn't had any issues besides intermittent hypertension. While her parents were showering her that morning in her hospital room, getting her clean for the ride home, she suddenly collapsed and became unresponsive. Within 4 minutes of that moment she was receiving chest compressions from the PICU chief.

137 minutes of chest compressions, 8 boluses of epinepherine, 4 boluses of atropine, 4 boluses of bicarbonate, 3 doses of calcium, 3 cardioversions, 2 boluses of ibutilide, 2 IO lines, and a bolus of insulin later, there still wasn't a pulse. Since she was a previously healthy child and was remarkably stable during the course of her hospital stay and had started getting chest compressions so soon after her event, the decision was made to get her down to the PICU and put her on ECMO (cardiopulmonary bypass) in hopes that giving the heart a break would allow it to snap back into rhythm. She was wheeled down the hallway with my resident straddling her on the bed, continuing to give compressions.

Down in the PICU, her room was converted into a field OR, and the cardiothoracic surgeons arrive to prepare to get her on ECMO. I am standing outside the room, looking for more opportunities to help and absorbing the controlled chaos, when the chief turns to me and says:

"MedZag, why don't you relieve David from compressions. He needs a break and I think it would be a good experience for you."

My adrenals dump a massive load of catecholamines into my system. I somehow find a way to utter "Yes, sir."

During our "Transition to Clerkship Week" at the beginning of MS3, we were forced to re-certify in our healthcare provider BLS (basic life support) training. Which basically entailed kneeing on the hard ground in dress clothes for 2 hours doing practice compressions on blue plastic mannequins which looked like they got misplaced from the set of I, Robot. There was no way I could predict that in 6 short weeks, my mannequin would suddenly morph into this brown-haired little girl.

I gown and glove up and go and relieve the fellow doing compressions. I was determined to do everything exactly correct - probably a delusional desire in the given circumstances, but I became fixated on a study I remember reading where residents and medical students who were instructed to do chest compressions to the beat of the Bee Gee's "Stayin' Alive" were much more likely to hit to target heart rate.

"Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive. Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive."

The surgeons incise in her neck and begin to dissect down to the carotid artery, a difficult prospect as with every thrust of my palm down into the little girl's ribcage, her neck jerks and blood flies into the air.

"Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive. Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive."

I become fascinated by how strong her ribcage is. Sweat begins to bead on my forehead, my respirations steadily quicken, and my arms begin to burn as the lactate accumulates in my muscle tissues.

"Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive. Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive."

This little girl was going to make it. She was supposed to go home today. This will be a fantastic experience to look back upon. I had images of the thank you card the PICU will receive when she starts first grade - the little girl grinning in a photo, missing her front baby teeth. The little girl who nearly died but now has her entire life, a full and rich life, to look forward to.

"Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive. Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin alive, stayin alive."

Bypass in on. Her body is once again receiving fully oxygenated blood. Chest x-ray shows everything is properly in place. Her heart regains a rhythm. Sinus. But 45 seconds later it fades. Asystole.

A repeat echocardiogram would eventually show a massive saddle embolus in her pulmonary arteries. You can't get blood to the body if blood can't get to the left heart. MRI and clinical exam showed absence of all reflexes and fixed, dilated pupils. There would be no first grade photograph.

I was in the room for the conference with the patients. Our chief explained what had happened. The scene felt surreal.

When stepping out of the room, one of the residents broke down in tears. The chief stares off into space. His words resonate in my head.

"Hope and pray that you never have to do that enough in your career that you get as good at it as I have."

Bypass was stopped 2 hours later. Within minutes, the brown-haired little girl, who should have been home watching cartoons, had passed on.

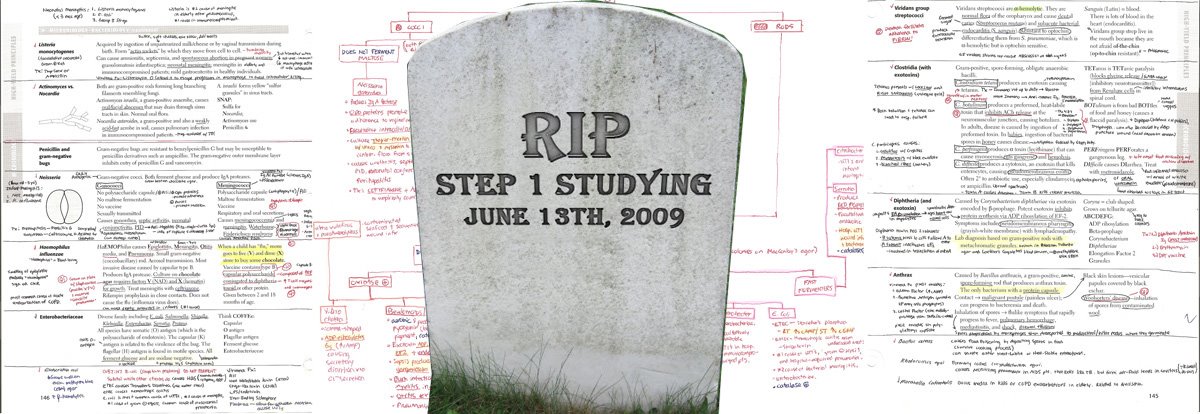

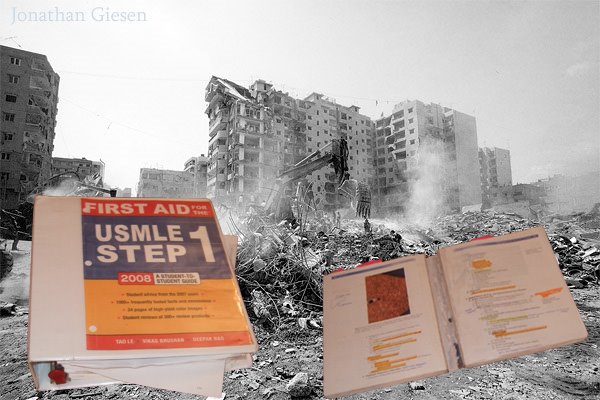

I was sent home to study for my shelf exam. I sat starting at my question book, but no studying would be happening that night. I logged onto the EMR and looked at her chart again. I looked at her echo again. I read the note I had written on her earlier in the week when she had been in the PICU. We had been instilled with the proper fear of a saddle embolus during our first two years of med school, but this was the first time I had seen one clinically and wanted to make sure all the information about the situation was seared into my brain. But mostly I simply sat there. And thought. I couldn't shake the feeling of guilt clawing at my stomach. This will be one of those centennial moments of my medical training: the first time I actively participated in a code, the first time I performed CPR on a patient, the first time I witnessed a truly horrific conference with parents, the first time I saw a member of the team collapse in tears, the first time I watched a patient die without forewarning. This was an important day in my medical career. But it is a sadistic reality that my education requires bad things to happen to good people.

So, to the patients of that little brown-haired girl: Thank you. Through your tragedy, I gained valuable experience that one day may perhaps enable me to save someone else's life. And know that I would gladly exchange all that experience for a picture of your daughter, clutching her pink backpack, grinning with her missing front teeth, on her way to start the first grade.